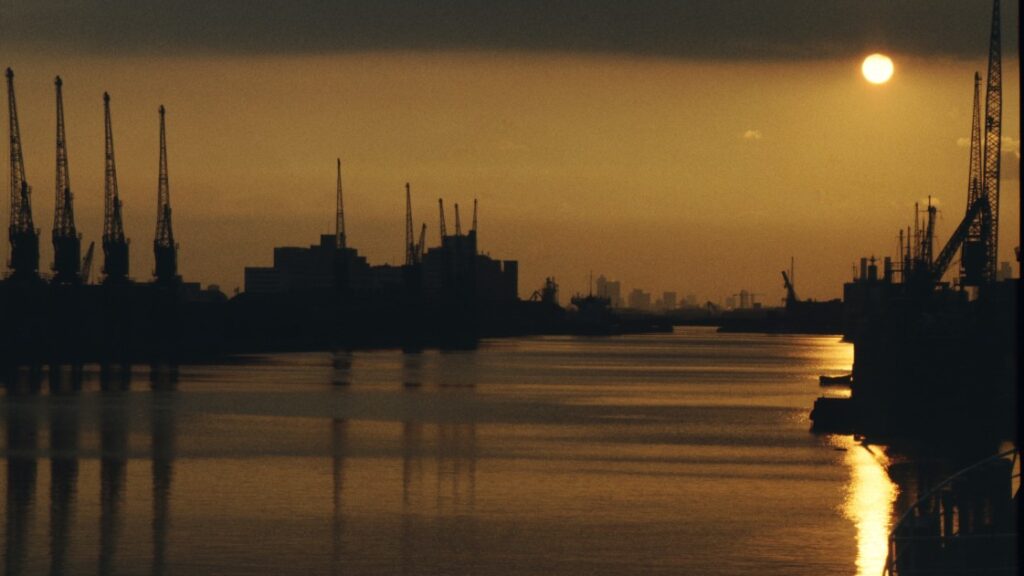

3. Living for the City

(credits to Ed Cox for the amazing image of London docks pre redevelopment)

One of the most written about shifts supposedly catalysed by the pandemic is the looming urban flight of the professional classes. Mastheads from Politico to The Guardian and The Telegraph have recently run variants on the theme of the escape to nature with a particular focus, as is often the case, on London. There are a number of reasons why this is overly-simplistic and is unlikely to be the case. The partial uncoupling of ‘city–as-economic-unit’ from ‘city-as-physical-social-network’ will make London a more vibrant, more textured and perhaps less unequal place.

For many, London is a necessary evil. The lure of work, particularly ‘middle class’ professional jobs means that many people cram in for the economic opportunity that would rather be in towns or villages. I have known many people, grudging residents of London – not Londoners – who while away unhappy years never taking much advantage of world-class clubbing, or free ballet performances, 10-quid West-End show tickets or just a walk along the Thames. Now this ‘white collar proletariat’ has a chance to unshackle itself from those chains.

Of course, there is more to the city than it’s professional classes. But their departure will accelerate geographical diffusion of the skilled service sectors – the baristas, barmen and brewers that keep London sane. We can already see vegan Deli’s in outer London suburbs; expect some of these London emigres to take their taprooms with them; urban tastes will mix with the de-hipsterfication of ‘nice things’ – no one wants bad coffee – finally ending the perceived urban monopoly on 11 pound pints and beard oil (anyone ever notice how self-consciously male so much of this stuff is?). This is nothing new; this was Brighton in the 90s, and more latterly places like Margate. Don’t be surprised if towns with great train links for 2 days a week in the office, great city centre housing stock and good quality schools such as Bedford or Basingstoke or smaller spots in the stockbroker belt like Oxted start to attract a younger, pre-family demographic in their late 20s, and with them, their cafes and sourdough bakeries, sitting comfortably alongside existing traditional (non-ironic) butchers and hardware ‘levelling up’ the locavore scene in these places. Less genteel (‘edgy’) spots such as Gravesend or other Medway towns could provide alternative options for early-career workers, looking to make the most of first-job wages as they plan their next move.

Don’t however, expect this exodus to be one-way. As pressure is lifted from the city with the departure of the ‘have to be heres’ and their financial muscle, there is more scope for the ‘want to be heres’ to come. With reduction of office space and the pruning of the white collar work, there is a chance, with the right incentives to make the city more diverse. Artists, musicians and all those who benefit from cultural agglomeration effects of the city will have more scope to return; the kind of people that in the past acted as an accidental ‘thin edge of the wedge’ for scavenging property developers and ended up displaced by the cultural capital created by their own success.

As someone raised a Londoner, clutching an old paper travel card, who remembers 50p bus fares and the opening of the Tate, taking myself on the train to school (in South London, real London, there was and is no Tube) I am hopeful. I am looking forward to a more passionate and engaged London, where those who previously priced the willing out, buy themselves an exit instead. What I am hopeful for is a city with fewer residents who resent being here and more space to breath, financially, culturally and socially for those of us who choose to make it home.