2: The Inflection Point was Long Ago

Society often struggles to name an era until after it has passed. And so it’s the same with social change; it doesn’t register until it has passed. The global Coronavirus pandemic has brought into sharp relief shifts that have been a long time coming. It is too easy top reduce the effect of this virus to a simple cause-and-effect when the reality is it’s more like a forest fire clearing out the deadwood so that we can see the new growth that was already there.

The acceleration of working from home is of course the most obvious of these shifts. The only people who have tried to predict the complete death of the office with a straight face are writers and freelancers who have been sitting in their converted attics for the best part of the last decade or two, but since the mid 00s a number of factors have led to the point now where it is a viable option. Faster internet connections and better video conferencing software are one element, but the shift for many to freelancing and “flexible” work in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007-2008 forced upon many their first taste of life beyond the office. Though the vast majority of those pushed out of work were very happy to regain the stability of permanent roles, few wanted the same rigidity. Whilst the world’s biggest tech companies continue to invest in HQs and showpiece campuses, that bring people together to work on the collaborative elements of their job that no video call will ever really replace, there is a consensus across sectors that a greater level of flexibility will be the norm. The pandemic is simply the final acceptance of this amongst the professional classes.

In the UK, the crisis in the hospitality industry has been covered widely, but for many of the pubs and venues that go to the wall, Covid-19 is the last in a long line of abuses. In the ten years to 2018, more than ¼ pubs closed. Britons had already decided staying in was the new going out long before going out became the new staying in; cheap supermarket booze, increased interest in weed and other ‘beyond alcohol’ choices, an ever broader range of leisure and social pursuits that we could pursue from our sofas (Netflix only began streaming in 2007 the same year that iPlayer launched and WhatsApp’s first release was 2009) as well as the growth of health and wellness as both a marker of status and a hobby pursuit. Add in increasingly restrictive clauses reguarding noise and ‘nuance’ for live music venues in gentrifying inner city neighbourhoods (…if you don’t like noise, get the fuck out the city) has meant that the industry was already poorly placed to weather this storm. After our initial excitement that the pubs have reopened, with many people claiming to crave a ‘proper pint’ that they hadn’t actually had in years, how many will stay in a plexiglass pub booth rather than go back to a perfectly mixed martini at home for less than the price of a short?

The ‘cashless’ society is another ‘no-shit’ shift. It was close to being a done deal before the pandemic, but the ‘rona has been the final nail in cash’s coffin. For years, decades even now, the convenience of cards had been superseding cash. Despite many small retailers’ resistance, under the false assumption that the card service charges were losing them money, without factoring in the time and inconvenience of cash – bank runs, cashing up, keeping your revenue on premise. For a while now the 50p fee or the minimum transaction has been looking retrograde amongst the few small vendors that clung to it, and there have been a number innovations that have sped this up. Challenger banks have made banking easier for businesses… but more difficult for cash when there is no branch. Payments services like Square make taking cards far more straightforward than legacy systems and also force long standing incumbents to level up. Add to this a generational cohort that has always had plastic in their pockets who are, on the whole, even more frightened of this virus than their parents, then the transition becomes irreversable.

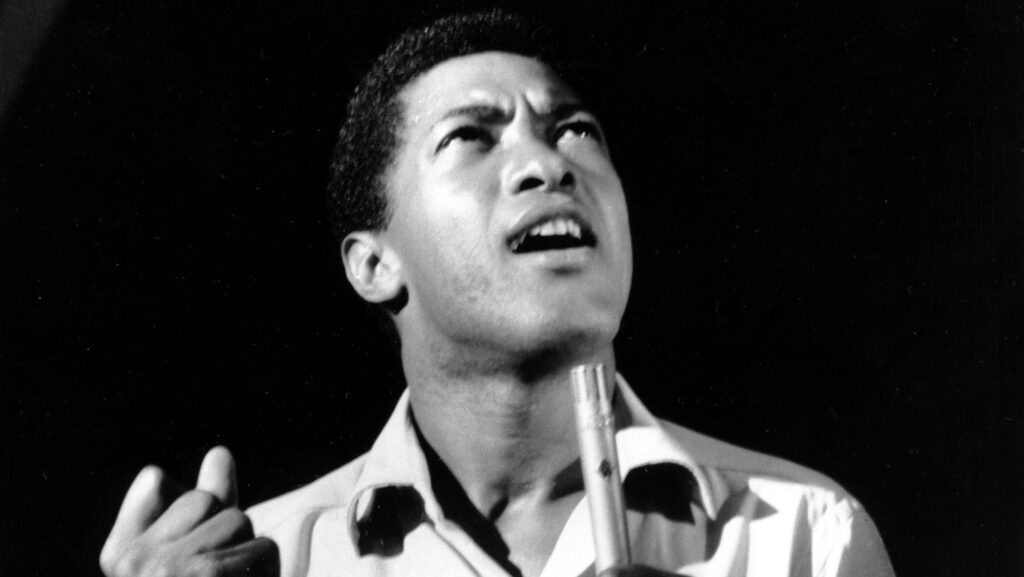

Thinking beyond the glib marketing speak of disruption and innovation, the pandemic will be remembered as the moment when the Black Lives movement in the USA broke not just into the America popular consciousness, but into the global lexicon. This in itself led to some strange dissonant moments – Singaporean acquaintances, posting black squares on their feeds, right next to posts blaming their own virus outbreak on migrant workers lack of hygiene rather than the unspeakable dormitory conditions in which they are made to live… and not seeing the contracition. Racism is a global problem, and every country has their own version of ‘black lives’ but Black Lives Matter does not easily fit into each country’s own problems. Without critical appraisal of the meaning of that particular movement and how it’s demands recontecxtualise within different socio-cultural contexts, it is in danger of losing the momentumn of its initial global impact. But we live in a reductive and globalised world, and that is a nuanced argument. However just because this movement ‘blew up’ in 2020 does not mean that it has not been years in the making. It can trace its lineage to Dr. King’s unanswered calls for economic redress, to the Republican Southern Strategy, or less obliquely to a cohort who began to examine systemic racism in the wake of Trayvon Martin in 2012. Even following this direct path, it’s 8 years in the making if not 400. The virus meant a critical mass of unemployed and underemployed young people, college students home from class and ‘WFH’ liberal 30- somethings were primed and able to act when George Floyed was brutally murdered. It’s painful to think that the phrase ‘I can’t breathe’ first rose to some kind of prominence with Eric Garner (2014) but took 6 years to become part of the popular consciousness.

I am a historian, or at least my degree alleges I am, and the further I have strayed from that starting point, the more I find myself coming back to the past as a way to understand the present. Which I guess is the point, else I’m just another antiquarian. Change is a slow process, punctuated by events that provide waypoints and landmarks that help us realise how far we have come. The pandemic is as much a marker as it is an event in itself. But more than that, it is a catalyst. Ideas and changes that have been long-gestating are birthed into the world by inducement of this crisis.

Category: Uncategorised