A History in 10 & 1/2 Haircuts

Kool Kut, Loughborough Junction, 2023

Last week, I went for a haircut. This might seem like an unremarkable opening, but the journey to the chair that gray Friday afternoon was both fraught and circuitous. As I hurtle towards early middle age, my hair is beginning to thin and keeping hold of it, and what it means to me is important.

I hate “As a…” writing. In fact, my entire family has stubbornly declined to be defined by ‘As A’ even with our Caribbean roots, and deeply mixed heritage. For me, this is all legible through hair. I have no interest in announcing who I am with an ‘As A’ every time I walk into a room, but my hair is a passive nod to so much of what has made me. My mixed race is not a badge of identity, so much as a statement of fact. Whilst in danger of sailing dangerously close to OJ (As in his infamous ‘I’m not Black, I’m OJ’ quote, not the more infamous domestic abuse and murder ) territory, I am more likely to tell you that ‘I’m an intellectual snob’ or ‘I’m a cyclist’ before I tell you that ‘I’m mixed race’. That’s not to say the last of these things has not been a fundamental part of what has shaped me, but it alone has been neither definitive nor determinative; it has sat alongside growing up working class, son of a single mother, and then the whiplash of scholarships to private schools and three years at an ‘elite’ university, or latterly, six years living in East Asia. Of course race matters, but it is both a fact and a construct, and honestly, I grew up in a family environment that strove to look beyond it in order not to be defined by it.

Within this context, as a light skin mixed race man who grew up around women and sounds a little like the BBC until he attempts a ‘th’, I find finding a barber, where I feel comfortable, difficult. Though the hair fits, I don’t have the patois, the braggadocio or the finer appreciation of the Premier League to participate in the tropes. It’s not that it’s unintelligible, it’s more like the performance is a game for which I know the rules but have little aptitude. I find it entertaining to watch, just don’t sub me onto the pitch. Some London barbershops are fine with this. Others are not. And it’s usually not until I am sitting on the chair, wrapped in the polyester cape with the clippers buzzing round my head that it becomes apparent which I am in.

In the wrong chair, what should be a reaffirming experience becomes one that alienates.

Thankfully Kool Kut were very ‘cool’ about it all.

Kosmos, Streatham, 1990

The first haircut I remember was at a Cypriot barber near where I grew up in Streatham. He had a black chipboard plank that he’d place on the arms of the barbers chair before helping me up onto the raised seat. I don’t remember much about the haircut but I remember enjoying being the centre of his focus for those 20-odd minutes. He had a sharply trimmed white beard and a gently receding hairline in matching white. I assume my mother chose that barber because he was ‘the barber’; next door to ‘the greengrocer’, across the road from ‘the bank’ and round the corner from ‘the baker’. It was the very end of the 1980s and the dying embers of the kind of unvarnished local shopping precinct that is now sought after and knowingly recreated in zone two neighbourhoods that estate agents have recently bestowed the honorific of ‘village’ upon.

My first hair memory though predates this. I remember sitting in my buggy in a graffiti covered lift heading up to someone’s flat in a (probably now a much desired now ex-)council estate in Knights Hill. In that front room, on furniture covered in thick clear protective plastic sat at least half a dozen women, along with at least twice as many children, playing and crying and napping about them. The air was thick with conversation, laughter and the burnt-hair smell of hydroxide straightening chemicals. I remember waiting. In my mind, we were there for hours waiting in this front-room Afro salon. It seemed that ‘getting my hair done’ for my mother was ‘waiting’ elevated to a high art form.

My adult self could speculate about the lives of these women, the small victories and troubles and consolations they might have been sharing, or how they scraped together the crisply straightened notes that paid for these hair treatments; not a luxury but a necessity to face all that they had to carry. But all I knew is that in that space, that distinctly feminine space, hidden away in that spotless flat, they were happy, and once her hair was done,

Despite all the other things she had to do, that might never be done, my mother was happy.

Starsky’s Barber Hutch, Tooting, 1993

There must have been something I recognised, seeing my mother in that particular space, like a shared secret, that made me feel like I needed my own version of, because as I got a little older, I was pestering her to take me to a barber of my own choosing; Starsky’s Barber Hut. In truth, I didn’t choose Starsky’s. There was a boy at my Primary School who had the Mortal Kombat dragon cut into the back of his ‘fro which I had become mildly obsessed with. The barber? Starsky’s. Considering how violent the video game was, it didn’t seem like the most age-appropriate trim – I never would have been allowed to play the game and we could never have afforded the console anyway, but nonetheless, I wanted in. Gamely, my mother agreed to take me, and though I was banned from any of the more ornate hair designs that were popular at the time, I didn’t care; I was going to Starsky’s.

I can remember the Saturday morning she took me. Like that front room in Knights Hill, it was black space, but unlike that front room, it was an unabashedly male space. As we took a seat in the ‘queue’ and the RnB crackled and bounced out from the half-busted, bass-boosted speakers, what I felt was less anticipation and more apprehension. It must have been an equally intimidating space for my mother, these black men, performing their pantomime of West Indian maleness tinged with what I now know to be the insecure misogyny that seems to linger in male dominated spaces from barbershop to boardroom. Eventually my hair was cut. She paid. We left.

I never went back to Starsky’s. Part of me wanted to. Or wanted to want to. My hair fitted, instinctively this was somewhere I should belong, but I didn’t. Was I not ‘black enough’? Did I just not sit easily with its masculinity? Was it simply the petty snobbery of my family; these were the kind of folks that we would pejoratively refer to as ‘back-a-yard’ people; my grandmother preserving a very particular lower-middle class snobbery of empire even as she migrated to the working classes of the mother country when she came over in ‘62. The next time I needed a cut, I went back to Kosmos. At least I felt welcome.

Jo Hair Design, Mitcham Lane, 1999

Jo’s opened on Mitcham Lane a year or two after I had started secondary school. It was probably the closest I ever got to finding my own version of that front room in Knight’s Hill. Jo, was a light-skinned Jamaican guy who must have been in his early 50s when he opened his shop, but I think if someone had told me he was 35, or 65, I would have believed either. Jo’s barber shop gave off a much more relaxed vibe. Probably closer to gentler, island stereotypes that those who only see the Caribbean through the rose-tinted lens of tropical fetishisation might recognise. Perhaps it was generational – he was closer to my grandmother’s cohort than mine, those who had seen the end of empire and the initial optimism of independence and distanced themselves from the street violence that the War on Drugs exported to Jamaica in the 80s and 90s.

This was the Jamaica – at least in spirit – of the independence era, the one that chose the motto ‘Out of Many, One People’ when it left the Empire and joined the Commonwealth, the Jamaica that trade union leader Alexander Bustamante would become the first Prime Minister of. My great-grandfather left Jamaica around 1960, with my mother leaving in 1962, aged four with my 22 year old Grandmother. (“on a plane, Adam, not a boat”). When John “Robbie” Robinson went back in the 1980s to retire, swapping a five-bed in Stockwell for a big house with a mango tree in the hills around Kingston, that Jamaica was gone. Taking him for a glass of red wine during his last visit to the UK in the late 00s when he was in his 90s, he told me to never go back. My mother’s great aunt, Edith Nelson, worked with Bustamante and would go on to be assistant General Secretary of the Jamaica Workers Union, work for which she received an MBE from the Governor General on Queen Elizabeth’s behalf in the 1968 New Years Honors list. I was related to Jamaican Labour royalty. But since the politricks had descended into paramilitary violence it was unlikely that anyone in our family would be heading back to claim our throne. It was an imagined Kingston of these myths that Jo’s shop took me too, with old Kung Fu movies permanently playing on a small black and white TV above the mirrors and his half-drunk Supermalt on the counter.

As I prepared for my exams, so did he, and around the same time I got my A-levels, he completed the plumbing course that I had been helping him with, his sometimes halting literacy a reminder of Papa John’s complete inability to read. Hair’s loss was plumbing’s gain.

‘Black Skinhead’, Oxford, March 2006

At university, I was all over the place, and in all truth, so was my hair. There were team buzz-cuts for sports events that made us look like starving convicts, and unruly plaits executed on lazy, stoned evenings by bored college-mates. I can’t really remember where I got my hair cut, or really if I had it cut that often at all. I hated that skinhead though. Cut right to the skin in the midst of a bitterly cold false spring, preparing for my boat race against Cambridge in the ‘lightweight’ rowing sub-category (“rowing for the physically impaired” as one obnoxious full blue referred to it). We were lean, angry and hungry and we (I never quite divined from where this general will had emerged) wanted hair to match.The week of the race in a farmhouse kitchen on Crazies Hill, we sat on a dining chair, and, one by one, each of us were shorn.

Though not every one of us. I remember one or two holdouts. At the time, I ridiculed them but now looking back, I admire them, and I think at the time I probably envied them. I wish I hadn’t felt the need to fit in so acutely, to subsume myself into an elite little collective, to belong. Not just that crew (though rowing isn’t the most obvious choice of sport for a kid from Streatham) but that whole institution. I desperately wanted to fit in, ideally by standing out, like all the other insecure extroverts that littered the university’s quads. Arguably it was those that blended in that stood out. The quiet assured type pursuing their passions, who were a little more sure of their preferences, who knew themselves well enough to be able to say ‘I don’t know’. That haircut was an act of supplication, my ‘fro a votive offering to the eternal proctors. Maybe I was overcompensating after trying too hard to ‘fit in by standing out’ in my first year. I had tried to ingratiate myself with the self-described ‘good lad’ crowd at my college, but it never really worked. I was thrown out of undergraduate accommodation at the end of my first term for one too many late night parties, trying too hard to make myself the centre of something.

I loved rowing for the Oxford Lightweights. It gave me a claim to the place and that claim gave me license to find my place within it. I settled into a happy groove between the rowers and the ravers and formed a close group of friends with a few others who resolutely wouldn’t be pigeonholed. I stopped trying so hard to perform and began to experience the place. And after that skinhead, I let my hair find its own way too.

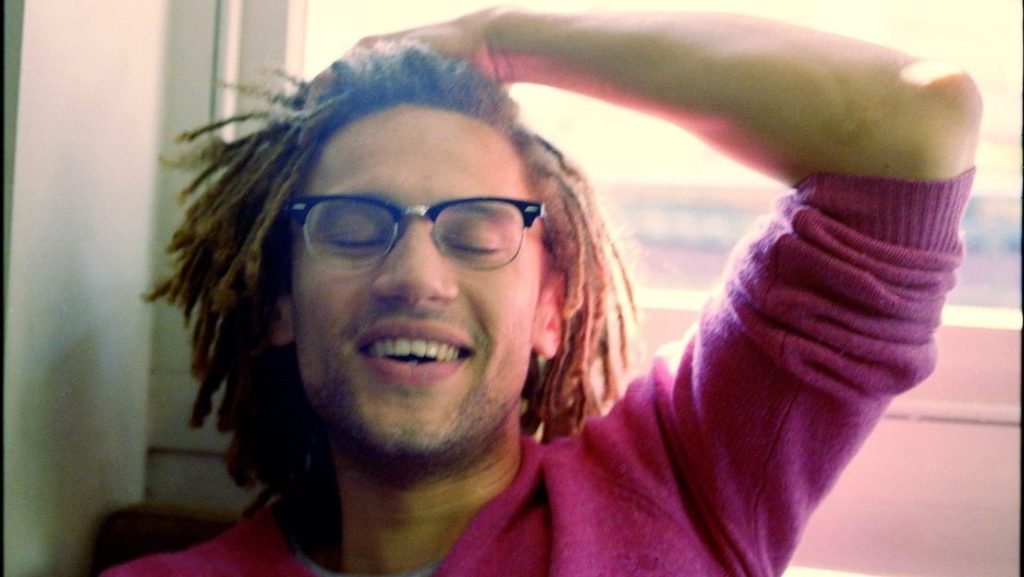

Dreadlocks, Self-styled, 2008

The second half of my three years at university were far more enjoyable and far less choreographed. I grew my hair out with no clear purpose or intent. I think someone plaited it for me one stoned Saturday afternoon as it was something to do while we did very little. My BBC English was still (and still is) flecked with MLE and still lacks those ‘th’-es much to my Malaysian partner’s amusement, but generically middle-class sounding enough. In the bleak midwinter, I probably looked pale enough to pass to the majority of my peers who had grown up outside the UKs major cities, so my hair was my marker; to explain the complementary and contradictory things that made me who I was. Left to its own devices over my last years at Oxford, my hair dreaded itself into a glorious mop of even, natural locs; no wax, no interlocking, just the occasional absent minded twist from me. I’d riff off my own hair, juxtaposing different linguistic codes and pieces of my own experiences across class and culture to avoid being labelled; when people got close to reducing me to one thing, I’d duck and wheel around, confounding the assumption they were just about to make. My locs were the internal gyroscope that gave me this social agility.

I revelled in that insider-outsider status, the ability to bait and switch across class codes and racial assumptions that let me wrongfoot so many. I’d used it to my advantage since my mid teens and it had been particularly useful when it had come to dating at university. My relationship with my heritage is very much a personal one; of course It sits in a wider context, but everyone’s story is an assemblage of parts. I truly don’t believe anyone is one hundred percent anything. It’s just less obvious to those that are in the middle of the arbitrary discrete boxes that nationality and race and all the other lies that bind, have drawn on a continuous field of humanity.

It’s why I never joined ‘BlackSoc’ while I was at Oxford, or the Oxford African and Caribbean Society, to give it its formal name. I am sure it played an important role for some people, but to me it looked like a dating agency for people who felt unable to date outside of racial lines. I found its proper name even stranger. Where and when I grew up, there had been a half-joking, though sometimes quite vicious edge between Caribbean and African folks, driven by different histories of migration, intersectionality of class, and the complex shadow of the ‘sell-side’ of the slave trade. Not everyone in the Caribbean looks at history through a Garvian worldview.

University can be a lonely place, especially if you see yourself – or are seen as – an outside. Race is an obvious vehicle for both alienation and belonging, but there are so many other intersecting ones when it comes to the ‘uni experience’ in Britain that I didn’t feel it as this all-encompassing trump card in the same way as I might if I had grown up in the US. The “blackest” person I knew at Oxford was an Old Etonion who is now a very diligent and very successful Tory MP. If he ever takes a run at PM, I don’t know if I would vote based on some shared bits of phenotype alone. Lovely chap though.

Abraham’s Barber, Reliance Arcade, 2014

I grew my dreads out through my mid 20s a few times. Had I known then, that a decade later I’d be struggling to grow it out at all, I would have savored the carefree abandon of young hair more. In 2014, I was living in central Brixton with a girlfriend leftover from the end of university. Inertia and a very good deal on rent had held us together longer than we should have been. I was an awful partner and we both wanted different things. We’d finally been forced to make a decision when it became apparent that she’d be leaving London for the next part of her career. We separated, I took an offer of a secondment to Singapore and I shaved my dreads.

My locs had become a dendrochronology of the chapter I was leaving behind. Suddenly they felt heavy with the weight of all the fuck-ups of my 20s. The meaning of symbols evolve over time, and suddenly my hair was the person I wanted to leave behind. Where once it had been a connection to my heritage, the locs now felt like a head of hedonism that I needed to shrug off. As I sat in the barber’s chair, a young-ish Caribbean woman berated the barber for committing the black on black crime of “cutting off a rasta’s dreads”. But as Andre 3000 asked: “Is every nigga with dreads for the cause? Is every nigga with golds for the fall?”

‘Barber Uncle’, Beach Road, Singapore, 2016

Moving to Singapore was a visceral experience of how coding changes in context. I was an anglophone westerner turning up to work a well paid middle class job. I was immediately thrown into the box marked ‘expat’. Singapore is an extraordinarily dissonant place. An open global city-state that propagates a chauvinistic nationalism that is defined by its status as the ‘little red dot’, a historic insult now worn as a badge of pride. It promotes a deeply conservative mode of identity that is also wholly cosmopolitan, not being defined by one single race or language. It’s ‘heartland’ resident – the true blue Singaporeans, complain about highly paid expatriates taking good jobs from locals, but their quality of life is sustained by the invisible bulk of foreign workers, the almost 1 million low wage, low skill Work Pass holders and Foreign Domestic Workers that make up the vast majority of the 1.3million foreigners working in a country of less than 5 and a half million.

Cycling around the island early on a Sunday morning, you’d see them getting their haircut at makeshift roadside barbers around their dormitory complexes, the triple-stacked, triple-bunk portacabins where these men from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Myanmar, would sleep between their shifts, driven from the dusty hinterlands of the island to the building sites of the downtown. Though I was an economic migrant too, it wasn’t the same for me. But if I couldn’t claim solidarity with them, I could at least distance myself from the champagne brunches and Bali weekends that were so typical for the gilded few that inspired the Singaporean citizens’ ire, so I tried to stand still and watch closer and listen more, to understand what made the place tick beyond the CBD. I’d always be an outsider, but I wanted to be an informed one.

In Singapore, I could feel faint echoes of the Empire that permeated through my own family tree. Guinness and heat. Condensed Milk. Broken English pieced into a new whole, Nahs and Lahs. So I spent time in the dense concrete suburbs that make up the majority of the country beyond the Grand Prix, Gardens by the Bay, Guidebook Singapore. I wandered HDB estates to admire the accidental Courbusier of the island’s public housing. I rode long MRT journeys to eat at Kopitiams beyond the condos. I wanted to balance my assumed neo-coloniser status with an affinity with another equatorial island. I got my hair cut for 5 dollars a time at various nameless barber shops in the bottom of 1970s housing blocks around the island, struggling all the while to find a decent fade. The best of the bunch was an old Chinese Singaporean man with a suspect mullet cutting under an old ceiling fan in an open-fronted store with a single chair in the back of Beach road. It was a better option than Toni & Guy.

Tanah Merah Complex, Singapore, November 2018

The most significant haircut I had in Singapore was my last. It’s also the least important to this history. On my third morning, I received a number one all over along with a half-size plastic toothbrush and the number; S5906. But that’s a story for another time.

Slot Afro Barber, Mirador Mansion, Kowloon, April 2019

After Singapore. Southern China. My partner was working for a major Chinese tech firm so I moved in with her, behind the Great Firewall, splitting my time between Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Commuting once a week between the PRC and the SAR in the midst of the Hong Kong protest movement was a surreal experience, straddling these ‘two systems’ that a shared lineage of centuries of culture and commerce across the Pearl River Delta, but were now like twins adopted by radically different sets of parents. Though it was being brutally eroded, the chaotic, cosmopolitan spirit of Hong Kong was a stark contrast to the stage-managed set pieces of Shenzhen’s luxury automated authoritarianism.

Shenzhen was a fascinating and hugely impressive place to live but also unsettling. From our apartment we could see as much of the city as the haze would allow, stretching 80 kilometers east to west, and only 10 deep North-South. The city snakes laterally, littorally, between the hills of the Hong Kong border, along Shenzhen Bay to the Pearl River delta. When night falls, the entire town lights up like a circuit board, streaming with steel and light. The immaculately kept, perpetually swept, cycle path along the Dasha river just next to where we lived was filled with office workers on dockless rental bikes, hired by the half hour, headed to one of the city’s many tech clusters, downstream, deeper into Nanshan district. The city had phased out almost all the old taxis, replaced with a fully electric fleet. The same for the buses. Pretty much every transaction, from street-corner noodles to legal fees are carried out through your phone’s digital wallets. This Cashless, silent, sleek panopticon acted as an equal and opposite of its ‘open’ neighbor and as a giant billboard for ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’; or more accurately, ‘Capitalism Unencumbered by Democracy’.

My weekly commute would take me from Chinese acquaintances who wondered why Hong Kong people caused so much trouble, past the Nanshan stadium that had become a temporary military base as the protest continued, due to its proximity to the Shenzhen Bay bridge and the motorway that led to the heart of Hong Kong Island, and on to an office in North Point where many of my young colleagues would come into the agency coughing from teargas attacks by police the night before.

During my two years in China, I became mildly obsessed with podcasts. My partner’s work took her all across the country and I would often have days where the only people I spoke to were Ira Glass (this American Life) Nate, Galen and the crew (fivethirtyeight) or Lionel, Richard and Daniel (The Cycling Podcast) I learned a little Mandarin, but those voices along with my mid-weekly trips to the office kept me sane in an otherwise luxurious but lonely existence. Crossing the bridge to Hong Kong also afforded me a few other things that I couldn’t get in the PRC; my half a week late Weekend FT, boozy Wednesday night chats with Jambo at The Pontiac, as well as a proper haircut. In a run-down little three story mall in Kowloon, Slot Barbers was in a second floor unit, run by a few of Hong Kong’s African diaspora and drew a crowd that ranged from Stock traders who had taxied over from the Island to transhippers off to the Canton Fair, diplomatic-looking types in sweat wrinkled suits through to dealers in dark streetwear taking a break from the night shift in LKF. It wasn’t the best haircut and it certainly wasn’t the cheapest, but I felt more welcome there than I ever did at Starsky’s and they gave me something precious I could walk through customs with when I crossed back to Shenzhen.

RnB Barber, Mitcham Lane, Streatham, 2021

Completely unconnected, I moved back to the UK at the start of the pandemic. We spent the first six months living with a good friend of mine from university, whose wife was stuck in the US, leaving him rattling around five bedrooms in central Brixton. He was kind enough to make it seem like we were doing him a favour, but as the early summer of April 2020 wore on, I knew how lucky we were for the space and his extended hospitality. The three of us took turns cooking, my partner painted, I got a job I hated to get a mortgage we needed for a home we wanted.

By September 2020 though, after an extended summer escape to Spain, it was time to end our overstay. I moved into a flat owned by my uncle in Streatham, directly underneath the one that I had grown up in with my mother and that he and my mother had both been brought up in by my grandmother, who after living for more than two decades in America had returned to Britain and to that same flat that had been leased by my family since the 1960s.

To me, it felt like some kind of symbolic defeat. I had gone so far to come back to quite literally below where I had started. Kosmos was under new ownership and Jo had already moved on. As we slouched towards our second Covid Christmas, the nearest barber, RnB, accommodated me for an overdue trim. I looked out on the same high street I had grown up on. The long-gone baker was a vape shop. At least there was some progress. I thought about my grandmother, who had raised my mother and my uncle mostly alone, the complexities of her stories, the violence of my uncle’s father, my mum’s time in foster care, the struggles of a single black mother in 1960s Britain aren’t mine to tell. We both had gone around the world only to come back. Only you can’t go back, you can only return, because neither the person nor the place are the same. My uncle had learned a few languages, moved to Paris, raised a family and was in the late prime of a varied journalism career. My mum had singlehandedly raised me and armed me with enough cultural capital to leverage my way to where I had got to so far. So many stories had spun out from that little flat in Streatham, even if I was in the same place, it was all new growth. I was engaged, getting married next year. We were waiting for renovation to be completed on a new home. I’d quit that job as soon as we completed. Sitting in RnB, that trim was a moment to contemplate all that. How far we’d all gone and how much was still to come.

Category: creative writing, personal